This Alaskan glacier holds back billions of gallons of water. Until it doesn’t.

This summer’s flood on the Mendenhall Glacier destroyed houses and displaced residents in Juneau. It won’t be the last.

By the end of that sunny Saturday in early August, Ballard had watched the Mendenhall transform into a terrifying torrent of gray glacial silt that ripped down towering fir trees, devoured dozens of feet of riverbank and washed away neighbors’ homes. That evening, she recorded the scene from her balcony, her voice almost drowned out by the roar of the water: “This may or may not be the last video I get to take from my porch,” she said.

This torrent of meltwater — normally held back by the giant glacier looming above Juneau — known as a glacial outburst flood, dwarfed any that have occurred since the phenomenon began here a dozen years ago.

The destruction has exposed just how unpredictable these floods can be, as glaciers around the world recede amid warming temperatures. Each year, more than a half-million people visit the Mendenhall Glacier, and scientists have a detailed understanding of how meltwater builds up and then pours out of it.

And yet, the magnitude of these glacial floods doesn’t tend to follow any clear pattern, fluctuating dramatically from one year to the next, said Eran Hood, a hydrologist with the University of Alaska Southeast in Juneau who studies the glacier’s dynamics.

Since many glacial floods happen in remote areas, there are “just so few long-term records,” he said. “These things are happening all over Alaska, they’re happening all over the world.”

Glaciers have unleashed deadly floods from the Andes to the Himalayas. Sometimes a dam of sediment left by receding ice will give way, causing a single flood. Other times, as in Juneau’s case, these outbursts can be recurring, based on the complex interplay between the changing glacier and the melt in tributary basins.

Some 15 million people worldwide live under the threat of sudden flooding from glaciers, according to a study published this year in the journal Nature Communications. As the climate warms, glaciers everywhere are retreating and meltwater lakes have grown in size and number, intensifying this threat.

Federal scientists and local academics have closely tracked the state of Mendenhall Glacier, and the water level in the abutting rock depression, known as Suicide Basin, that fills with snowmelt. They map and monitor the area with drones and remote cameras, and warn residents about potential floods.

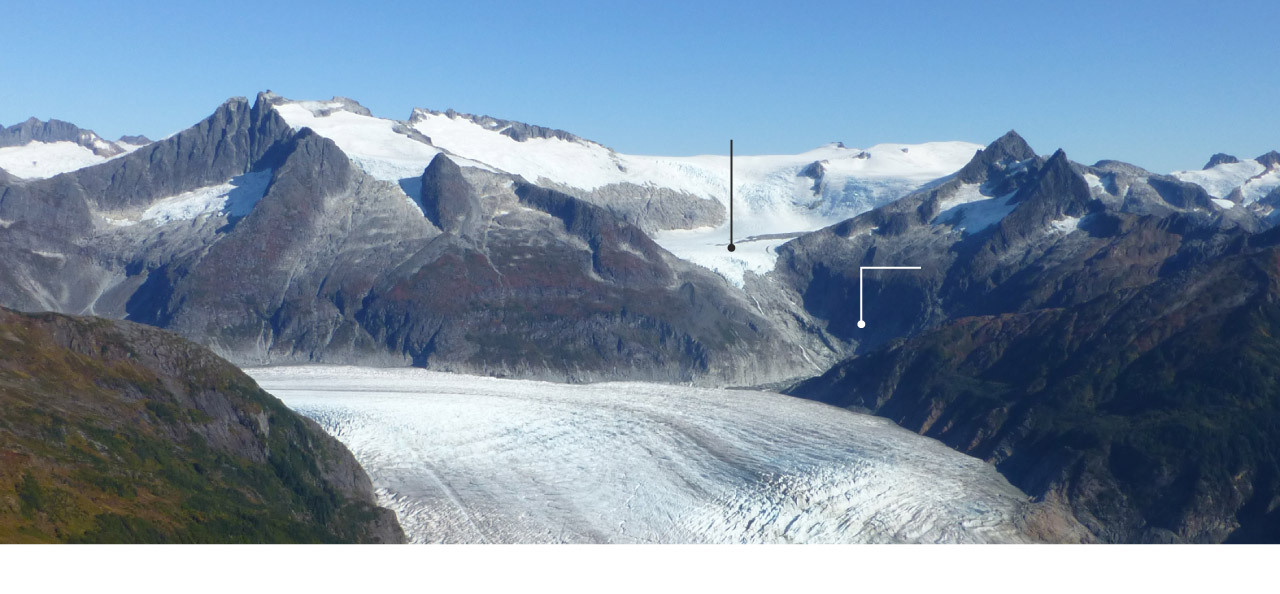

Suicide Glacier

Suicide

Basin

Mendenhall Glacier

Source: Christian Kienholz, University of Alaska

Southeast. Photo is from 2018.

Suicide Glacier

Suicide

Basin

Mendenhall Glacier

Source: Christian Kienholz, University of Alaska Southeast.

Photo is from 2018.

Suicide Glacier

Suicide Basin

Mendenhall Glacier

Source: Christian Kienholz, University of Alaska Southeast. Photo is from 2018.

And yet, the flood on Aug. 5 far exceeded forecasts by the National Weather Service or the worst-case expectations of homeowners along the river, releasing about 40 percent more water than the last record flood seven years ago. The river was flowing at more than six times its normal rate, hydrologists here said, an event that had just a 0.2 percent chance of happening — on the order of a 500-year flood.

“This was unprecedented seeing this amount of water come out,” said Aaron Jacobs, senior service hydrologist with the National Weather Service in Juneau.

Ballard and other neighbors had not been perched on the river’s edge, but set back at least 50 feet from the bank. They were not in a designated flood zone.

As the Mendenhall Glacier and its tributaries continue to melt, scientists are facing renewed urgency to understand this looming threat above Juneau.

Does Suicide Basin hold more water than scientists realized? Has something changed inside the glacier?

“The big mystery,” Hood said, “is why was the flood so big this year?”

‘Uncharted territory’

On the morning of Aug. 4, Jacobs was flying home from Sitka, Alaska, when a colleague texted him: “Got time for a call. Looks like the basin is going.”

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) gauge at Mendenhall Lake — at the foot of the glacier — was showing water levels rising sharply. Jacobs had been expecting this. All summer, a jumble of icebergs and meltwater had been filling Suicide Basin. And when it eventually flushed out, as it had done more than 30 times since 2011, the water would pour into Mendenhall Lake and down the river to Juneau.

From his office, Jacobs can track the status of the basin via a remote USGS camera stationed on the hillside, next to a laser that takes height measurements every 15 minutes. The glacier normally served as a dam for that reservoir of ice melt and rainwater, but when enough of it accumulated, the tremendous pressure could lift the glacier and let water escape underneath.

This was known as going “subglacial.” When that happened, Jacobs said, the passageway within the glacier can rapidly expand, emptying billions of gallons of water downstream in a matter of hours.

There were signs that moment was approaching. In late July, two of Hood’s colleagues had taken a helicopter up to the basin. Standing on a rock face overlooking the swollen lake, they launched a drone that took more than 1,000 overlapping images that help create a three-dimensional elevation model of the basin and estimate how much water it might hold at full capacity.

About a week later, water began overtopping the ice dam and flowing down along the glacier’s flank.

When this overtopping had happened in two previous years, the water found its subglacial escape hatch about a week later. But each year the glacier is changing, and the holes made the summer before may be gone. No one knew exactly when it might burst.

On Aug. 4, with lake levels rising, the National Weather Service issued a warning predicting that Mendenhall Lake would peak the following evening around 10.7 feet — about five feet above its typical level.

Jacobs was out the next day talking to residents and observing the raging river as water levels surpassed that initial projection and then kept going beyond the 12-foot record set in July 2016. Before the night was over, it would rise three feet higher.

“We’re in uncharted territory,” he recalled thinking.

A ‘tough house’ destroyed

Steven Peterson came to the same conclusion when he watched the current sweep away a towering Sitka spruce near his deck that had stood for decades.

“It just started cutting that bank away like Swiss cheese: shoo, shoo, shoo,” he said.

Peterson, 80, had built much of his 7,500-square-foot house by himself when he retired from Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game two decades ago. In the garage was his beloved wood shop — where lately he’s been making duck decoys for Christmas presents — and above that a two-bedroom apartment where tenants lived.

Peterson evacuated at about 10 p.m., and within an hour the river had ripped away the wood shop and apartment.

A few days after the flood, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) toured the damage along the river. She stopped by Peterson’s home as he and his daughter picked through the wreckage.

Peterson told her he wanted to demolish the damaged house, stabilize the bank and sell the property so someone else could build on a safer portion of the property.

“You sound like a pragmatic Alaskan,” Murkowski said. “Stuff happens and we’ve got to do something.”

“You don’t solve anything by crying,” he said.

Inside, however, the weight of what he had lost was hard to ignore. The room with his handmade bar now opened onto the rushing current. Peterson climbed a ladder into the room from below to retrieve his doctoral dissertation about long-tailed ducks in the Arctic. He took his collection of single-malt scotch, too.

A fire alarm was incessantly blaring as he packed up canned food. He surveyed the warped floors and walls riddled with cracks. At least some of it was still standing.

“Oh well,” he said. “I built a pretty damn tough house.”

He had also been fastidious about labeling his things. In the days since the flood, people have been calling from all over with his belongings. One person found a gun case; another his vacuum-packed halibut. The backpack he used for clamming washed ashore in Tee Harbor.

And someone even called from Portland Island, four miles out to sea, to report that a duck decoy with his name on it had just made landfall.

An ongoing issue

Three days after the flood, Hood flew back to the glacier to map the changes in the drained basin.

He was stunned by the view.

“When I got up there, I said, ‘Oh my god,’ it’s much lower than it has been in the past,” he recalled.

The jumble of icebergs on the surface had fallen some 500 feet. But it was still difficult to know precisely how much water the trough could hold.

When USGS hydrologic technician Jamie Pierce began monitoring the basin more than a decade ago, he bolted pressure sensors onto the rock wall that would get submerged as the water level rose — to estimate depth. But when the basin emptied during floods, plummeting ice sheared the wall.

“The icebergs would crush our stuff,” Pierce said.

The remote camera-and-laser system he built has worked better, but the depth of the ice and the internal plumbing of the glacier remain elusive.

Using models from before and after the flood, Hood and his colleagues estimated that 14 billion gallons escaped in the torrent.

The mapping also revealed that melting has extended farther into the Mendenhall Glacier than previously known. And that the rate icebergs are melting within the basin is accelerating, he said, adding more water.

The basin also drained more fully than in the past.

“The estimates for volume we had didn’t account for that because we’d never seen that before,” Hood said.

Since the Mendenhall Glacier began shrinking in the mid-1700s, it has retreated more than three miles, including some 800 feet between August 2021 and August 2022. The rate of retreat depends on various factors, but scientists say the rapid loss is due in part to human-caused global warming in recent decades.

While the severity of any given outburst flood is guided by the interplay of the glacier and the basin, “the overall mechanism for these types of events is caused from a warming environment,” Jacobs said.

At some point in coming decades, when the Mendenhall Glacier recedes past Suicide Basin, these floods will no longer be a problem, although other basins may flood from higher up on the glacier. For the time being, the problem is expected to continue each summer.

“It’s likely that we haven’t seen the biggest one yet,” Hood said.

Lives upended

If that happens, Ballard and her twins won’t be on the river to see it. Her condo, condemned after the flood, was eventually cleared for her to return. But she doesn’t plan to live there again.

“I don’t know if it would ever be safe,” she said.

On the evening of the flood, Ballard scrambled to collect clothes, medicine and baby formula as firefighters evacuated her building. She spent the night with her aunt.

Throughout, she was texting and calling her friend Elizabeth Kent, a fellow teacher on leave while she taught English in Nicaragua.

Kent’s three-bedroom home, next to the condo building, stood more than 100 feet from the river, but the flood swept all that away and demolished her home.

She now owes hundreds of thousands of dollars for a mortgage she can’t pay — with her tenants also displaced. The estimate to stabilize the bank on her property is another $120,000, and the state assistance she might qualify for would cover only about one-third, she said. Her insurance company has denied her claim and is offering nothing. She is facing bankruptcy.

The fact that her home was not in a Federal Emergency Management Agency flood zone was one of the reasons she bought it three years ago. The home was just so far from the water, she never thought it could be at risk.

Maybe this was that unlucky once-in-500-year moment, she said. Or maybe more is changing in ways that are harder to understand.

No comments:

Post a Comment