Russia recruited operatives online to target weapons crossing Poland

Russian spy agencies built a network of amateurs for operations including sabotage, assassination and arson — plots disrupted by Polish authorities

Within weeks, recruits were tasked with scouting Polish seaports, placing cameras along railways and hiding tracking devices in military cargo, according to Polish investigators. Then, in March, came startling new orders to derail trains carrying weapons to Ukraine.

Polish authorities now believe that the mysterious employer was Russia’s military intelligence agency, the GRU, and that the foiled operation posed the most serious Russian threat on NATO soil since Moscow launched its invasion of Ukraine last year.

Russia’s objective was to disrupt a weapons pipeline through Poland that accounts for more than 80 percent of the military hardware delivered to Ukraine, a massive flow that has altered the course of the war and that Russia has seemed helpless to interdict, according to Polish and Western security officials.

How military aid gets to Ukraine

Military deliveries

coordinated from 50

donor nations

Military aid between

Jan. 24, 2022, and

May 31, 2023.

1

U.K.

OTHER

U.S.

GERMANY

The International Donor Coordination Center in Wiesbaden in southwest Germany is the “nerve center” for military aid for Ukraine.

Arms deliveries do not physically pass through, but the 100 personnel who work there have organized the delivery of 150,000 tons of materiel.

$6.6B

$17.9B

$42.8B

$7.5B

INTERNATIONAL

DONOR COORDINATION

CENTER

To Polish ports and airports

2

20%

At first, when donations largely consisted of smaller weapons such as Javelin antitank missiles, many of the supplies arrived by air to a regional airport in Rzeszow near the Ukraine border.

But as more countries began shipping heavier weapons systems including HIMARS, tanks and cruise missile systems, rail, land and sea routes into Poland have become more important.

Delivered

through other

countries

80%

Delivered

through

Poland

UKRAINE

To the Ukrainian border

3

Poland and Ukraine coordinate “last mile” deliveries across the border, which often happen at night. Decoys and other methods of deception can be used, while larger deliveries can be broken down into smaller units to better avoid detection.

To the front line

4

Supplies can reach the front line in as little as 48 hours. No longer on NATO territory, the journey to the battlefield poses the greatest risk of disruption. But while warehouses of weaponry have been targeted, Russia is not known to have hit a major military cargo shipment.

Source: Kiel Institute

SAMUEL GRANADOS / THE WASHINGTON POST

Instead, the case has become another damaging blow to Russia’s spy services, whose unfounded assessments that Kyiv could be easily toppled shaped the disastrous invasion plan, and whose once-pervasive networks across Europe have been uprooted by waves of expulsions and arrests.

The plot in Poland marked an attempt to reverse this slide. Unable or unwilling to rely on its own operatives, Russia assembled a team of amateurs, including by using Russian-language postings on Telegram channels in Poland that are frequented by Ukrainian refugees, according to Polish officials, whose account was confirmed by their U.S. intelligence counterparts.

The Russian Foreign Ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

Had it succeeded, the scheme might have paid off on multiple levels — slowing weapons deliveries while fanning resentment toward the 1.5 million Ukrainians who have fled to Poland since the start of the war. Even in failure, the downside was limited for Moscow, with mainly displaced Ukrainians, rather than GRU operatives, ending up in Polish prison.

Senior Polish officials said the plot crossed a dangerous threshold. “This is the first sign that the Russians are trying to organize sabotage — even terrorist attacks — in Poland,” said Stanislaw Zaryn, who oversees the country’s security services, in a recent interview with The Washington Post.

The case also has political sensitivities for Warsaw, where officials have not publicly acknowledged that 12 Ukrainian refugees are among those in custody, anxious to avoid the backlash Russia likely intended. Others arrested include one Russian and three citizens of Belarus.

In interviews, officials emphasized said that while most of the Ukrainian suspects were from eastern provinces traditionally more aligned with Moscow, they appear to have been motivated more by money than ideology.

Investigators have since uncovered evidence that Russia was planning other, deadly operations. Recruits had been tasked to carry out arson attacks and an assassination, said an investigator directly involved in the case for Poland’s domestic security service, the ABW. The investigator would not discuss the targets.

“This threat was eliminated, but the broader threat remains,” said the investigator, who, like others, spoke on the condition of anonymity, citing security concerns and the sensitivity of the case. Russia’s spy services remain active in Poland, he said, and “will try to eliminate the mistakes they made.”

Details about Russia’s use of the popular Telegram app to recruit operatives and the extent of the attacks the GRU was allegedly pursuing have not been previously disclosed.

The Poland plot mirrors the outsourcing model long employed by terrorist groups including the Islamic State, using online methods to recruit operatives and direct distant attacks aimed at sowing panic in the West. It represents a significant departure for Russia’s spy services, including the GRU, whose operatives were directly involved in the attempted poisoning of a Russian defector in England in 2018 and explosions at ammunition depots in Bulgaria and the Czech Republic.

This article is based on interviews with more than a dozen security officials in Poland, Ukraine and the United States, as well as information from documents, suspects’ social media accounts, and interviews with relatives and associates of those arrested.

One of those suspects, Maria Medvedeva, 19, was detained while traveling extensively around Poland with a boyfriend, Vladislav Posmityukha, who has also been charged with espionage. Her father, Pavel Medvedev, said in a recent interview with The Post that the photos they posted on social media prompted him to ask how they were paying for their excursions.

His daughter explained that Posmityukha had cryptocurrency accounts holding “money received from Russia for some actions,” Medvedev said. “She said that he was doing something at a high level and wasn’t telling her.”

Outsourcing operations

The derailment plot in Poland was set in motion at a time when Ukraine was planning the counteroffensive it launched in June, and powerful new weapons systems, including German-made Leopard tanks, were making their way toward a narrow band of Polish highways and rail tracks that act as a funnel for deliveries.

EST.

SWE.

Baltic

Sea

LAT.

Moscow

DEN.

Gdynia/

Gdansk

LITH.

RUS.

Minsk

RUSSIA

Berlin

POLAND

BELARUS

Warsaw

GERMANY

Major crossing

points

Kyiv

Rzeszow

CZECH.

REP.

Lviv

UKRAINE

SLVK.

AUSTRIA

Front line

MOL.

HUNGARY

ROMANIA

CRIMEA

Black Sea

200 MILES

These shipments have risen sharply in volume, range and lethality since the start of the war, drawing comparisons to the “lend-lease” flow of American military hardware across the Atlantic in World War II.

Over the past 16 months, the United States and nearly 50 other countries have delivered more than 150,000 tons of materiel — equivalent to the weight of 1,000 Boeing 747 aircraft — to Ukraine. Lightweight munitions sent at the start of the war have given way to tanks, HIMARS rocket launchers and Storm Shadow cruise missile systems. The United States alone has committed more than $43 billion in military aid, according to the Pentagon.

The vast majority of this materiel has passed through Poland not only because of its strategic position on Ukraine’s western border but also because of Warsaw’s defiant posture toward Moscow — a resolve shaped by a long history of conflict and hostility.

Russia’s inability to interdict this constant stream of lethal cargo, whether before it enters Ukraine or as it crosses the western half of the country, has baffled military officials and experts.

“It is astounding to me that here we are 18 months [into the war] and they have not been able to destroy a single convoy or train,” said Ben Hodges, a retired U.S. Army general who served as commander of U.S. Army forces in Europe. “Not one moving target has been hit.”

The failure reflects the severe shortcomings of Russia’s military, including a surprising inability to track or hit moving targets, as well as a perceived reluctance by Moscow to risk strikes in western Ukraine that could stray into Poland and ignite a response from NATO.

Russia’s struggle to stem the weapons flow is also part of the fallout from its flawed war plan.

Convinced that Kyiv would fall within days, Russia made no concerted attempt to destroy Ukraine’s extensive air defenses. As a result, Russia has since been unable to send fighter jets or other aircraft over vast stretches of the country that weapons shipments traverse.

“Since the outset of the conflict, multiple Russian lines of effort have failed to disrupt Western military aid deliveries to Ukraine,” read a top-secret slide circulated among U.S. military commanders in February. As a result, the document said, the United States and its allies have been able to exploit “a mostly permissive environment for continued lethal aid deliveries.”

Given these constraints, U.S. spy agencies warned in February that Russia was likely to seek ways to “sabotage logistic [sites] on NATO territory with plausible deniability,” meaning in ways that would be difficult to attribute to Russia, according to the document, among those included in a trove of classified intelligence reports obtained by The Post.

Outsourcing operations to Ukrainian and Belarusian nationals was one way to accomplish that.

The postings used to lure potential recruits were scattered among job offers, housing tips and internet scams that litter the Telegram channels frequented by refugee groups in Poland, officials said.

They promised pay ranging from a few dollars for painting a graffiti-like message to $12 for hanging a poster, said the ABW investigator. There were fliers and banners that said, “POLAND ≠ UKRAINE,” “NATO GO HOME” and “DO NOT BE BIDEN,” according to information provided by the ABW.

Distributing such material served two purposes, officials said: fanning anti-Ukraine sentiment in Poland but also testing recruits’ willingness to carry out assignments against the government hosting them.

Those who submitted photos showing they had done what was asked were given more dangerous assignments. Some were instructed to buy burner cellphones and cameras that would be passed via dead drops to other recruits who began crisscrossing Poland to file reports and photos from rail yards, airfields and seaports.

Recruits were paid in cryptocurrencies and wire transfers from untraceable bank accounts, officials said. In a measure of organizational zeal, the hidden sponsors of this work published their piecemeal pay rates on spreadsheets. At the top of the scale were the derailment, arson and assassination assignments, though even these were listed at only several hundred dollars, according to ABW officials.

Russia seemed to target recruits whose ages and backgrounds were less likely to draw the attention of security services, officials said. Most were in their 20s and one was just 16. By February, an organizational shape began to emerge.

“The operation was based on a classic cell structure,” according to information provided by the ABW, with cells focused on functions including surveillance, acquisitions, logistics and operations.

“Every cell had a leader, a trusted person of Russian intelligence services,” according to the ABW. Those at lower levels were kept in the dark and “did not know each other unless it was necessary.”

As the assignments escalated, even junior members of the network began to realize they were probably doing Moscow’s bidding, officials said. Some rationalized their involvement as relatively harmless or financially necessary, according to officials. Once on Russia’s payroll, they may also have feared that it was too late to back out.

Cameras in the shrubs

Russia has threatened arms shipments since the start of the war. Days into the invasion, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov warned that “pumping weapons into Ukraine” was not “just a dangerous move but an action that turns these respective convoys into legitimate targets.”

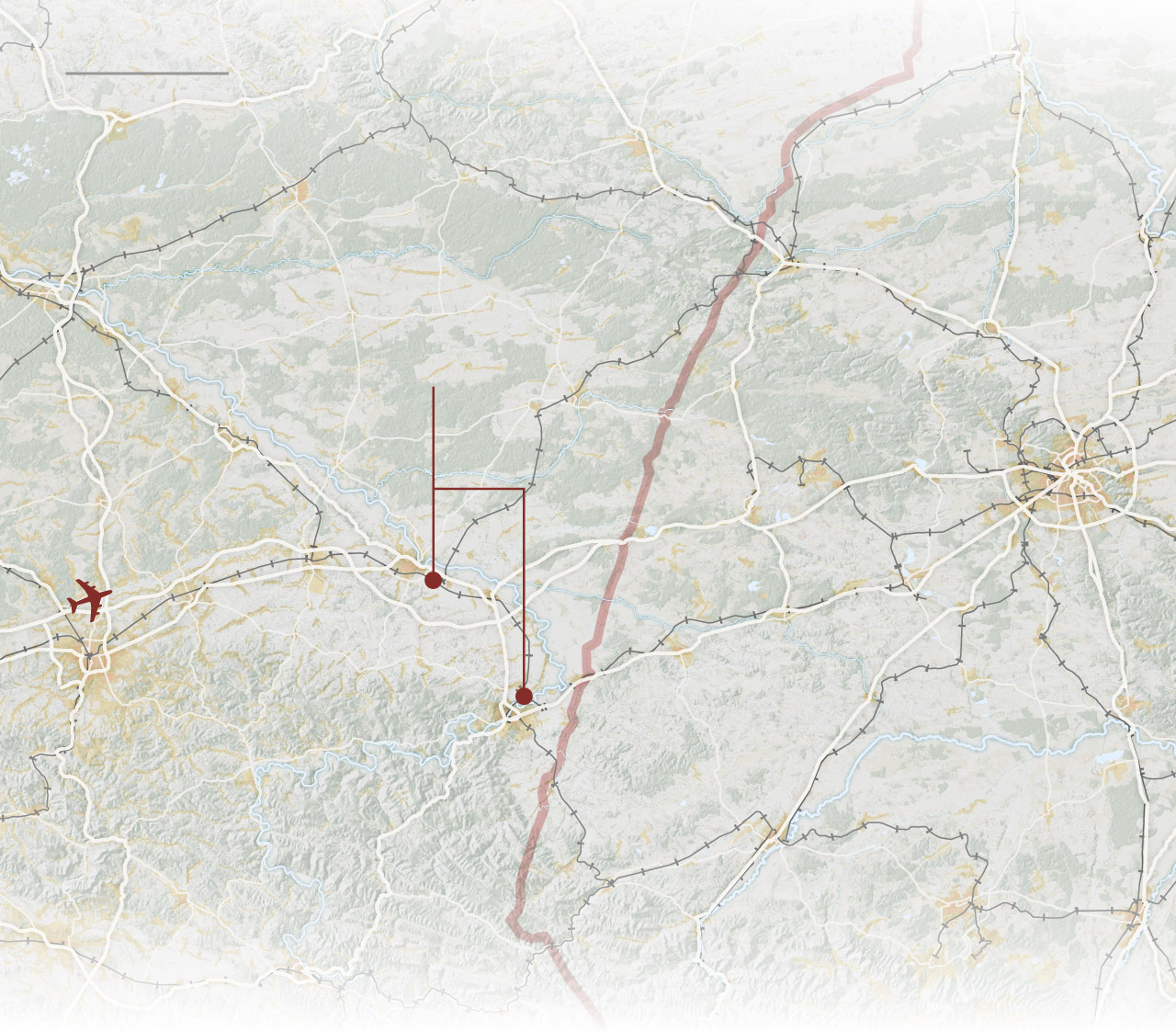

15 MILES

UKRAINE

Bilgoraj

Rava-Ruska

Locations where cameras

were uncovered recording

passing trains.

Lezajsk

Lviv

Yavoriv

Horodok

Jaroslaw

Mostyska

Rzeszow

Mykolaiv

Przemysl

POLAND

Sambir

Stryi

Drohobych

The United States has taken significant steps to deter attacks, deploying hundreds of troops from the 10th Mountain Division and Patriot antimissile batteries to the Rzeszow-Jasionka Airport, about 65 miles from the border with Ukraine. The once-quiet airstrip has served not only as the main hub for weapons deliveries but as a way station for world leaders including Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, who has used the airport for nearly every foreign trip since the war began, and President Biden, who landed there on Air Force One in February on his way to Kyiv.

The region is crawling with clandestine security. Poland has deployed hundreds of agents to safeguard transit links and border crossings that are also monitored by Western drones, spy planes and satellites, officials said.

And yet, the Russian sabotage ring went undetected until a passerby noticed a camera lens peeking out from the trees and shrubs along an important stretch of track and reported the discovery to authorities, officials said. The device, an off-the-shelf video camera using solar power, was transmitting footage of passing cargo to an online repository that could be accessed remotely with the correct password.

Using data from the camera, mobile phone records and nearby cellphone towers, investigators were able to determine not only when the device was installed but who had been in the vicinity at that time — one of several apparent tradecraft slips by Russia’s poorly trained recruits.

Searching other sections of track turned up additional cameras at locations that authorities showed to The Post: one on the trunk of a poplar tree near a bridge where trains have to reduce speed, another in branches overlooking rail sidings where cargo cars are shunted while waiting for tracks ahead to clear.

Within days, authorities had a suspect in custody who “gave us information about other members of the group,” including his handler, the investigator said. Surveillance, intercepts and other steps led to additional members and cells.

Polish officials said their initial plan was to monitor the network to learn more about its intentions and chain of command. But officials said they were forced to abandon that idea after intercepting messages that indicated a plot to derail weapons shipments was already underway.

Investigators found detailed instructions that had been sent to one of the network’s cells for placing derailment devices on locations of track where trains moving at even modest speeds could be sent plunging off the rails, officials said. The officials asked that the nature of the devices not be disclosed.

The ABW investigator said that at least two recruits had signed on to carry out the attack and that a location and time were set. He acknowledged that authorities did not find the devices in searches at multiple sites, and said it remains unclear whether the operatives had obtained them and hidden them elsewhere.

Improvisation and desperation

Polish authorities said there are still significant gaps in their understanding of the network, including the identities of the Russian operatives directing it and the full extent of their encrypted communications with cell leaders in Poland.

The few documents that have surfaced publicly allude to some of these investigative blind spots. A diplomatic cable Poland sent to the Belarusian Embassy reporting the arrests of Belarusian citizens alleges that they were part of a cell run by an individual known as “Andriy,” whose identity was not known at the time.

Court records for the case are classified, and the names of those arrested have not been released. Polish officials declined to say where they are being held or who is representing them in closed-door court proceedings. Ukrainian officials, including the country’s ambassador in Warsaw, also declined to answer questions about the case.

Some information has surfaced about three Belarusian suspects whose names were published in state media reports that proclaimed their innocence and castigated Poland for their arrests.

The Belarusian couple taken into custody fits what Polish authorities described as the preferred profile for the GRU recruits: young, able to travel Poland without suspicion and eager to make money.

Medvedeva, one of the suspects, moved to Poland last year to study journalism in Warsaw, her father said. Her social media history — replete with selfies at the gym, Starbucks and shopping excursions — betrays no sympathy toward Moscow or its client government in Minsk. She appears in videos taking part in anti-government demonstrations in Belarus in 2020. A post from March 2022 shows a vase of tulips in the Ukrainian colors of blue and yellow with a broken-heart emoji.

Medvedev said he supported his daughter’s move to Warsaw but urged her to end her relationship with Posmityukha, a Belarusian who Medvedev said is 10 years older. Their relationship appears to have begun at least three years ago in Minsk, according to social media posts.

Attempts to reach relatives or a lawyer for Posmityukha were unsuccessful. Speaking to Belarusian state-controlled Belteleradio earlier this year, Posmityukha’s father, Oleksander, called the charges against his son “crazy nonsense.”

“Yes, he has his own vision of what’s going on in the world, but he hasn’t been seen to have any such desire to engage in illegal activities,” the father said.

Medvedev said he covered his daughter’s tuition and living expenses in Warsaw, but that photos the couple posted online suggested other sources of cash. When pressed for details about their finances, Medvedev said that his daughter told him that Posmityukha had “asked her to open a cryptocurrency account and a bank account in her name but did not allow her to use it.”

Instead, Medvedev said, Posmityukha controlled the accounts with passwords he did not share. He also traveled frequently, Medvedev said, stopping to stay with Medvedeva at her dorm in Warsaw between trips to Belarus and Russia.

“She said that he worked for some Russian company,” he said. “He was traveling all the time, all over the place.”

The first indication of trouble came on March 5 of this year, Medvedev said, when his daughter didn’t call home as expected to wish her grandmother a happy birthday. Calls to check on her, he said, did not go through. A week later, he said, the family received a call from the Polish Foreign Ministry informing them that Medvedeva had been detained on espionage charges.

The two were arrested during a trip that took the guise of a romantic seaside visit, according to Polish officials, but allegedly had the aim of observing the Gdynia harbor just as a large arms shipment arrived.

They are accused of “conducting observations to gather information concerning critical infrastructure facilities,” including at the airport and rail station at Rzeszow and the seaports of Gdansk and Gdynia, according to diplomatic cables sent by Poland to Belarus and shown on Belarusian television. Pro-Russian leaflets were found in their luggage, Medvedeva’s father said.

After the arrests were announced on March 16, Belarusian state media went into overdrive, airing videos of interviews with family members who insisted the detainees were innocent.

Medvedev said his daughter is being held at a detention site in Lublin, and that she has been held for long stretches in solitary confinement. She has been visited by her attorney and her mother, Medvedev said. He said he did not know the lawyer’s name. The mother, who is divorced from Medvedev, did not respond to requests for comment.

“The situation is very, in my opinion, very crazy,” Medvedev said, adding that his daughter has had emotional breakdowns at the detention site. Polish law allows suspects in national security cases to be held for months without trial. Lawyers hired by the family have attended hearings and reported that Medvedeva “just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Medvedev said.

“She did nothing,” he said. “She’s just a witness, so they keep her.”

Polish officials disputed that. Medvedeva “was aware of the true nature” of the assignments she carried out with Posmityukha, according to the ABW. “She did not find it disturbing,” the agency said, and “benefited [from] the money” that Russia sent.

The work of the cells in Poland may have aided Russian attempts to strike arms depots and other storage sites in Ukraine — static targets that Russia has more success hitting, especially closer to the war’s eastern front. Ukrainian officials said that tracking devices have been found in weapons stocks targeted in Russian attacks several times over the past year.

Ukraine has also faced its own struggle to root out Russian informant networks, making hundreds of arrests. Among those detained was a rail worker in the eastern Dnipropetrovsk region who was arrested in February and accused of sending the coordinates of stations where weapons shipments were offloaded.

Ukraine’s military has sought to minimize its vulnerability to Russian strikes by using decoys, including mock-ups of the HIMARS rocket launchers provided by the United States, and breaking down shipments into smaller packages dispersed swiftly across the front.

Polish officials involved in the investigation described the case as unlike any other they have encountered, reflecting levels of improvisation and desperation on the part of Russian spy services facing unprecedented pressures.

After the invasion, Poland expelled every known case officer with Russia’s SVR, FSB or GRU spy agencies — 45 in total, officials said. Russia’s palatial embassy in Warsaw now resembles a ghost town. On a recent afternoon, no lights were visible inside and no one passed through front gates guarded by Polish police.

A senior Polish intelligence official said Russia has sought to salvage fragments of its espionage network by relying on deep-cover operatives who are not based in the embassy. “They are using their illegals, their sleepers,” the official said, adding that they are employed cautiously by the Kremlin because they are few in number and lack the legal protections afforded diplomats.

Moscow continues to enlist amateurs it sees as more expendable, officials said, and the investigation of the sabotage ring has led the ABW to other suspects. Among them is a 20-year-old Russian hockey player for a team in Poland who was detained in June after being caught surveilling Ukraine border crossings.

Serhiy Morgunov in Kyiv and Cate Brown in Washington contributed to this report.

No comments:

Post a Comment