MIAMI

On the worst days, when the backyard would flood and the toilet would gurgle and the smell of sewage hung thick in the air, Monica Arenas would flee to her mother-in-law’s home to use the bathroom or wash laundry.

“It was a nightmare,” Arenas, 41, recalled one evening in the modest house she shares with her husband and teenage daughter several miles north of downtown Miami.

She worried about what pathogens might lurk in the tainted waters, what it might cost to fix the persistent problems and whether the ever-present anxiety would ever subside.

Residents in neighborhoods around Arenas’s have similar tales to share — of out-of-commission toilets, of groundwater rising through cracks in their garage floors, of worries about their own waste running through the streets and ultimately polluting nearby Biscayne Bay.

For all the obvious challenges facing South Florida as sea levels surge, one serious threat to public health and the environment remains largely out of sight, but everywhere:

Septic tanks.

Millions of them dot the American South, a region grappling with some of the planet’s fastest-rising seas, according to a Washington Post analysis. At more than a dozen tide gauges from Texas to North Carolina, sea levels have risen at least 6 inches since 2010 — a change similar to what occurred over the previous five decades.

Along those coastlines, swelling seas are driving water tables higher and creating worries in places where septic systems abound, but where officials often lack reliable data about their location or how many might already be compromised.

“These are ticking time bombs under the ground that, when they fail, will pollute,” said Andrew Wunderley, executive director of the nonprofit Charleston Waterkeeper, which monitors water quality in the Lowcountry of South Carolina.

To work properly, septic systems need to sit above an adequate amount of dry soil that can filter contaminants from wastewater before it reaches local waterways and underground drinking water sources. But in many communities, that buffer is vanishing.

An estimated 120,000 septic systems remain in Miami-Dade County, their subterranean concrete boxes and drain fields a relic of the area’s feverish growth generations ago. Of those, the county estimated in 2018, about half are at risk of being “periodically compromised” during severe storms or particularly wet years.

Miami, where seas have risen six inches since 2010, offers a high-profile example of a predicament that parts of the southeast Atlantic and Gulf coasts are confronting — and one scientists say will become only more pervasive — as waters continue to rise.

Here, expensive repairs afflict homeowners as septic systems falter. Fetid water increases the risk of gastrointestinal diseases and other health hazards as floodwaters fill yards and streets. Profound worries persist about the environmental toll — which, researchers in Miami say, means submerged septic tanks are leaking nutrients into the porous limestone, potentially fueling algae blooms that kill fish.

“It’s really pretty gross,” said Michael Sukop, a hydrogeologist at Florida International University.

Rising seas will only exacerbate the problem, he added. “As the water table gets higher, all bets are off.”

Miami-Dade County is racing to replace as many septic tanks as possible, as quickly as possible. But it is a tedious, expensive and daunting task, one that officials say will ultimately cost billions of dollars they don’t yet have.

It also is far beyond a Florida problem.

In Georgia, officials have documented more than 55,000 septic tanks in counties near the Atlantic Coast in an ongoing data gathering effort. In North Carolina, researchers estimate, the discharge from approximately 1 million septic systems drains to waterways that eventually reach the ocean. In South Carolina, the issue has been the subject of legal fights and proposals in the state legislature.

In numerous states, researchers are studying the potential effects of what they call a largely unseen and unquantified environmental and public health threat.

“We don’t even know the scale of the problem,” said Rob Young, director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University. “I think it’s everywhere. And it can’t get better as long as sea levels are rising. The only question is how quickly it can get worse.”

An environmental mess

More than 700 miles north of Miami, Mike O’Driscoll is among the scientists trying to decipher just how quickly rising seas are driving water tables higher, and why that matters.

O’Driscoll, a coastal studies professor at East Carolina University, and several colleagues have spent recent years documenting how rising groundwater is altering the hydrology along the Outer Banks in North Carolina.

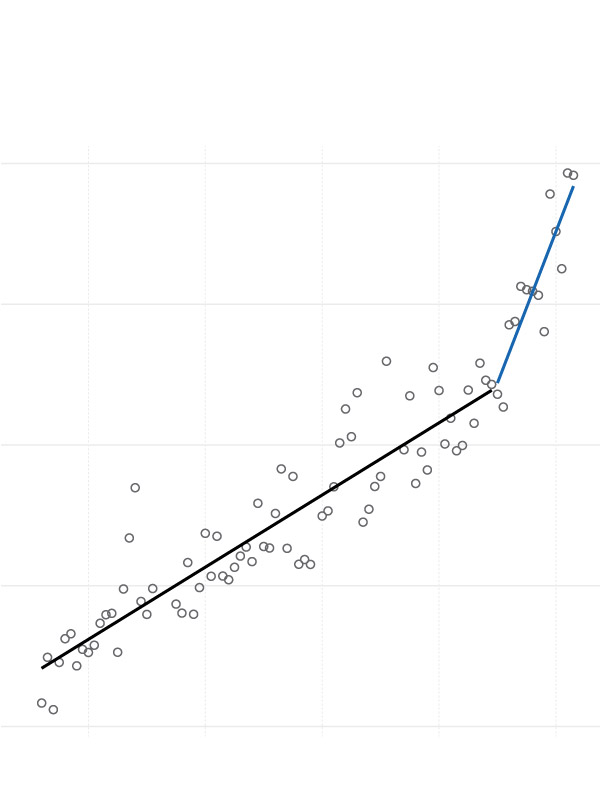

In Nags Head, the group installed technology to monitor nearly a half-dozen aquifer wells for fluctuations in groundwater levels. They compared their findings to similar data from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality stretching back to 1983, and a clear trend emerged: Rising sea levels are raising the groundwater.

“If you look around the Outer Banks, the groundwater has risen one and a half feet in some places,” O’Driscoll said.

North Carolina requires about a foot to a foot and a half of separation between septic drain fields and the seasonal high-water table, depending on the soil type. But in places, that cushion is dwindling.

The Drowning South

“Rising groundwater has started to inundate systems in low-lying areas,” O’Driscoll said. “Some may be failing right now, but within a couple of decades, in some places, it won’t be viable to use conventional septic systems anymore.”

Beyond the environmental concerns, O’Driscoll worries about the financial impact for coastal communities and residents. It can cost homeowners $30,000 or more to install more advanced on-site wastewater treatment systems, and it costs localities many millions to expand existing infrastructure.

The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that roughly 20 percent of households in the United States rely on septic systems to treat their wastewater. That figure rises to more than one-third of homes in the Southeast, according to the agency. Florida is home to an estimated 2.6 million such systems.

In some places, such as rural areas not served by a centralized sewer and not threatened by encroaching groundwater, the approach can work well and be cost effective.

When conventional systems work as designed, solids from a home or business’s waste settle within the septic tank, while liquid waste is discharged into a drain field — usually a set of perforated pipes designed to slowly release effluent into the ground. The soil acts as a natural filter, neutralizing disease-causing pathogens, and reducing nitrogen, phosphorus and other contaminants before it reaches groundwater.

But that process is under increasing strain as seas push higher in the region and torrential rainfalls become more common, a combination that can inundate buffers that once existed.

EPA-funded research in Maryland has shown that many coastal properties with septic systems, which already face significant flood risk, will become far more vulnerable in the coming decades. As more septic systems fail, said Allison Reilly, a University of Maryland civil and environmental engineering professor, the more widespread the consequences will become, disproportionately harming low-income and minority residents.

“Right now it’s an environmental issue,” she said, “but as we warm, we’d expect it to become more of a public health issue.”

‘We know what’s coming’

Roy Coley, Miami-Dade County’s top sewer and water official, stood in the backyard of a home on NE 87th Street one afternoon. Nearby, workers had dug a trench as they prepared to connect the house and others nearby to a municipal sewer line.

“You’ve got so many thousands to do, where do you start? You start with one,” he said. “These houses are the low-hanging fruit.”

Over the past several years, leaders in Miami-Dade have aggressively pursued federal and state funding to decommission septic tanks and connect homes to sewage lines. The homes along NE 87th Street, not far from the Little River, just off Biscayne Bay, were converted in part using a grant from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

Miami-Dade County said it has so far been awarded about $280 million in grants. About 100 homes have been converted, and workers have put in place the public infrastructure to connect another 775. Coley said the county also is trying various approaches to offset connection costs for homeowners, which average around $15,000.

“We are seeking every way in the world to ease that pain,” he said.

But it remains a herculean task. The county estimates that about 9,000 septic tanks already are vulnerable to compromise or failure under current conditions — a number expected to climb as sea levels rise. Coley said roughly 11,000 septic tanks are on the priority list for removal.

Eradicating septic entirely could cost more than $4 billion, the county estimated in 2020. And the future of the effort, officials said in an email, “is strongly dependent on identifying and securing funding sources.”

But Coley said there has been a key shift over time: buy-in from elected officials and residents.

“I think up until now, there was just a general lack of understanding about how failing septic tanks impacted the environment,” he said. But that’s no longer the case. “When you know better, you do better.”

The problem of leaky and failing septic tanks is hardly a new one in Miami, and the area’s geography and geology have always made them a risky proposition.

The author of a 1949 article in Look Magazine titled “Florida’s Polluted Paradise” detailed the estimated 150,000 septic tanks already around greater Miami, many wedged side-by-side in a region that is “prairie-flat” and hardly above sea level.

Even then, South Florida’s heavy rains often overwhelmed them. “I, myself, have seen septic tanks in numbers back up and overflow into lawns and onto sidewalks in residential areas, owning to the fact that the underlying ground was too burdened with sewage and water to contain any more,” wrote the author, Philip Wylie.

Two decades later, little had changed.

A 1970 report from the Federal Water Quality Administration found that as many as 800,000 people around the county relied on septic tanks, and that many waterways suffered from low oxygen concentrations and startling levels of coliform bacteria, which can signal the presence of fecal waste.

“Septic tanks, widely used in Dade County, are public health hazards,” the report concluded.

The federal government insisted the county develop a master plan to reduce sewage pollution and combat leaking waste from septic tanks.

Using hundreds of million dollars of federal money along with public bonds, the county did build new wastewater treatment plants to ease some of the pollution, but it was not a panacea. Today, there remain neighborhoods that are surrounded by municipal sewer service, but where most homes still rely on septic tanks.

“They were intended to be temporary in Miami, and here we are 50, 70 years later,” said Rachel Silverstein, executive director of Miami Waterkeeper, which has campaigned to end septic pollution.

“There’s water everywhere, and there’s nowhere for it to go,” she said one sunny morning as a high tide sent water sloshing over the bulkheads along Biscayne Bay.

As bad as the problem has been historically, there is one aspect long-ago planners did not factor in: sea-level rise.

“Septic systems were not designed with the assumption that groundwater levels would rise gradually over time,” found a 2018 county report, “and as a result many are not functioning as they were originally designed.”

That report emphasizes how elevated groundwater levels are creating an “immediate” public health risk. “There are also many financial and environmental risks, including contamination of the freshwater aquifer, which is the community’s sole source of potable water,” the study found.

In recent years, Miami-Dade Commissioner Raquel Regalado has led the charge toward trying to phase out failing septic systems in the county.

“I hate them all. I want to get rid of all of them,” the Republican lawmaker said of the old concrete tanks.

She spearheaded a moratorium on any new septic systems on county-owned properties, pushed to ensure that development within a certain distance of sewer lines be required to connect, oversaw rules that require more sophisticated, self-monitoring septic tanks when outdated ones must be replaced and supported trying to offset costs of sewer conversions for homeowners.

“We have to get ahead of this, because we know what’s coming,” Regalado said. “It’s an environmental disaster waiting to happen.”

‘It will keep happening’

The lawsuit came from two South Carolina environmental groups — the Charleston Waterkeeper and the Coastal Conservation League.

Amid a building boom, the groups claim, state regulators have failed to adequately consider the effects of sea-level rise and stronger storms when approving growing numbers of septic tank permits across eight coastal counties.

“[Their] failures place the public’s health at risk and expose our state’s waterways, marshes, beaches, and fisheries to significant, documented harms that can be traced to untreated sewage from malfunctioning, ill-maintained, and/or ill-placed septic systems,” one filing read.

The lawsuit, filed in late 2022, cites existing or planned housing developments in vulnerable areas, including several near the town of Awendaw, about 25 miles northeast of Charleston. There, the suit states, hundreds of homes built close together would rely on septic tanks, all near the Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge.

“A large percentage of the developed land is actually comprised of septic drain fields,” one filing argues, saying that such a situation risks “significant, irreparable harms” to public health and that of nearby marshes, beaches and fisheries. That includes the possibility of diseases such as hepatitis A and salmonellosis, which can be transmitted through fecal matter, and degradation of water quality, the filing said.

The groups want state officials to give special consideration to the cumulative impact of such clusters of septic permits. Already, they argue, South Carolina has no comprehensive inventory of existing septic tanks and little way for the public to challenge permits before they are approved.

“Sea level rise is happening. It will keep happening,” said Leslie Lenhardt, a senior managing attorney for the South Carolina Environmental Law Project, which is working on the case. “It’s steady, and it’s coming for these developments.”

In legal filings and in an email to The Post, the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control said that it follows current law, which requires the agency “to conduct a coastal zone consistency review of only those wastewater treatment systems and septic tanks that handle more than 1,500 gallons per day or handle other than domestic waste.”

The agency acknowledged that there is no database of all septic tanks in the state, and said there is “no legal authority” that requires public notice about pending septic permits — though anyone can request such information by email.

Data provided by the agency shows it has approved increasing numbers of septic permits in the state’s coastal counties: nearly 16,000 from 2018 through 2023, with the largest numbers in Charleston County.

Beyond the courtroom, other South Carolina officials also are attempting to change the status quo.

“Everyone is very proud of the natural resources around here, but it’s fragile,” said state Rep. Joe Bustos (R), whose district encompasses a coastal swath of Charleston County, an area where seas have risen 7 inches since 2010, according to The Post’s analysis.

Bustos has co-sponsored a bill, unpassed by the legislature, that would ban new septic permits within two miles of the coast.

Wunderley, the Charleston Waterkeeper, supports that legislation and has watched both sea-level rise and the area’s growth accelerate in recent years. “It’s creating this dual pressure that’s really hard to deal with,” he said.

The legal and legislative efforts in South Carolina offer a glimpse at the tensions that states and localities face as they confront the legacy of conventional septic tanks in coastal areas where seas are rising fast.

There are success stories, but none are cheap or fast.

In 1999, with evidence that water quality was deteriorating along parts of the Florida Keys, the state mandated that the island chain eliminate the use of tens of thousands of septic tanks and other outdated waste systems. The cost reached roughly $1 billion as Monroe County built centralized sewage and hooked up thousands of homes and businesses.

“There was a huge change in water quality,” said Coley, who spent a decade working for the Florida Keys Aqueduct Authority.

For years, Georgia has worked to compile one of the most robust databases of where its remaining septic systems are — an effort that at times has involved digging through handwritten permits in dusty county filing cabinets. The result is a detailed list that allows state officials to better understand the risks that exist, both now and as groundwater rises over time.

“There are places where septic systems are clearly unsuitable, and that needs to be factored into future land planning,” said Scott Pippin, an attorney and environmental planner at the University of Georgia’s Carl Vinson Institute of Government.

Skip Stiles, a senior adviser at the Norfolk-based group Wetlands Watch, said septic failures are “like a blinking yellow light” that foreshadow a wider set of problems. As waters rise, he said, it will raise wrenching questions where the problem already is shifting from a nuisance to a persistent hazard.

“It’s forcing that decision that all of us in coastal communities are going to face eventually, but some are already facing now: Do I stay or do I go?”

Buying time

Arenas and her family are among the first homeowners to benefit from Miami-Dade County’s race to replace the most vulnerable systems.

Last year, crews removed their septic tank and hooked their house into a nearby municipal sewer line. Overnight, the nightmare vanished. No more monthly calls to have her underground tank pumped out. No more fretting over toxic water in the yard, or racing to a relative’s house to use the bathroom.

“It is 100 percent changed,” Arenas said.

That remains far from the case everywhere.

Less than a mile away, in the quaint village of El Portal, where peacocks lounge on the steps of the municipal building and Spanish moss hangs from giant oaks, Elizabeth Fata Carpenter spent years worried about water rising underneath the community she loves.

Carpenter and her husband moved to the neighborhood in 2019, and their yard flooded on multiple occasions, undermining the septic system behind their 87-year-old house. Especially after heavy rains, water oozed from the cracks in their garage floor. Their overmatched drain field overflowed into their yard and across the patio. They carried their 70-pound dog to higher ground for walks, and kept boots nearby to wade to their cars.

“We know the floodwater on our property is septic tank water,” Carpenter said one morning last fall outside her home, steps from the Little River. “I know it’s flowing into the river, and not just from my house, but everybody’s homes.”

Earlier this spring, the couple sold the house and moved to Fort Lauderdale. But Carpenter remains as chair on El Portal’s sustainability and resilience task force. And as an environmental attorney, she continues to fret about the collective pollution caused by septic tanks.

El Portal Mayor Omarr Nickerson shares those worries, and is working to end his community’s reliance on septic systems. But there is an inescapable obstacle: money.

Nickerson estimates that it would take roughly $50 million to convert the homes of El Portal to the municipal sewer system. The village’s annual budget is about $2 million, he said, more than half of which goes to the police department.

The county has designated roughly $6 million to help kick-start the effort, Nickerson said, but El Portal also must compete for funding with dozens of other local governments.

He worries that the issue, if left unsolved, might not only pollute the bay, but eventually drive people from his community.

Walking the streets on a postcard-perfect morning, Nickerson points to houses where unseen troubles lie. Where toilets back up. Where sewage-tainted water sometimes swamps yards and driveways. Where homeowners keep sandbags close at hand.

“It’s just going to continue,” Nickerson said.

The mayor points out an easily overlooked clue about the changing landscape of his village. Outside some houses, unnatural mounds of earth rise from the otherwise pancake-flat ground — an unmistakable sign that an old septic tank has been replaced with a newer, elevated version.

Some mounds are unadorned. Others are neatly landscaped. One resident built an entire deck around what she called the “mountain” in her backyard.

Several years ago, the septic system behind Kristen McLean’s home along the Little River failed as groundwater filled the tank and rendered her plumbing useless. For weeks, she relied on a composting toilet while she had a new engineered system installed.

“When we dug the hole for that septic system, the groundwater was 18 inches below my lawn,” she said. “This little area is a microcosm of what South Florida is up against.”

McClean sold the house in 2021 and jokes that she moved two miles away but seven feet higher.

These days, the mound rising in her old front yard is ringed with native plants.

It’s now a butterfly garden.

About this story

Design and development by Emily Wright.

Photo editing by Sandra M. Stevenson. Video editing by Alice Li and John Farrell. Design editing by Joseph Moore.

Editing by Anu Narayanswamy, Katie Zezima and Monica Ulmanu. Additional editing by Juliet Eilperin. Project editing by KC Schaper. Copy editing by Phil Lueck.

Additional support from Jordan Melendrez, Erica Snow, Kathleen Floyd and Victoria Rossi.

No comments:

Post a Comment