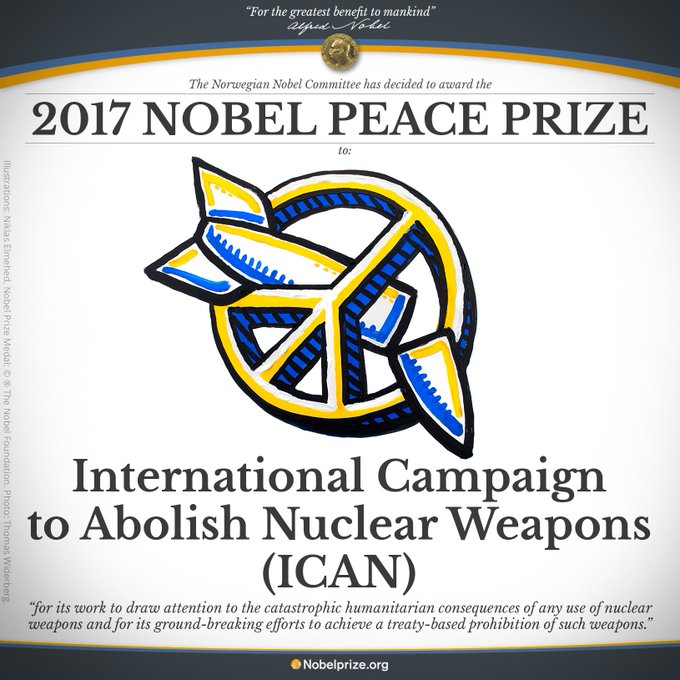

In a year when threats from nuclear weapons seemed to draw closer, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded on Friday to an advocacy group behind the first treaty to prohibit them.

The group, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, a Geneva-based coalition of disarmament activists, was honored for its efforts to advance the negotiations that led to the treaty, which was reached in July at the United Nations.

“The organization is receiving the award for its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and for its groundbreaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons,” the Norwegian Nobel Committee said in a statement.

The choice amounted to a blunt rejoinder to the world’s nine nuclear-armed powers, which boycotted the negotiations and denounced the treaty as a naïve and dangerous diversion.

It also represented a moment of vindication for the members of the winning organization, known by its acronym ICAN, and for the United Nations diplomats who were responsible for completing the treaty negotiations.

ADVERTISEMENT

“This prize is a tribute to the tireless efforts of many millions of campaigners and concerned citizens worldwide who, ever since the dawn of the atomic age, have loudly protested nuclear weapons, insisting that they can serve no legitimate purpose and must be forever banished from the face of our earth,” ICAN said in a statement.

The United States, which with Russia has the biggest stockpile of nuclear weapons, had said that the treaty would do nothing to alleviate the possibility of nuclear conflict and might even increase it.

The committee acknowledged the view held by nuclear-armed countries in its statement, noting that “an international legal prohibition will not in itself eliminate a single nuclear weapon, and that so far neither the states that already have nuclear weapons nor their closest allies support the nuclear weapon ban treaty.”

Despite those admonitions, at least 53 member states of the United Nations have signed the treaty since a ceremony to start the ratification process was held at the General Assembly on Sept. 20. Delegates representing two-thirds of the General Assembly’s 193 members participated in the treaty negotiations.

“We have received this news with so much joy,” Elayne Whyte Gómez, the Costa Rican ambassador to the United Nations in Geneva, who was the chairwoman of the negotiations, said in a telephone interview. “Every year there should be at least one happy event to give us hope, and this was it.”

She said ICAN’s work “represented efforts by civil society activists who approached governments around the world and maintained the momentum of the negotiations to keep them going.”

Dr. Ira Helfand, a disarmament activist and board member of the Physicians for Social Responsibility, one of ICAN’s founders, called it “a powerful voice reminding us all of the urgent need to ban and eliminate these weapons as the only reliable way to make sure they are not used.”

The treaty will go into effect 90 days after 50 United Nations member states have formally ratified it. As of Friday, three — Guyana, the Vatican and Thailand — had done so.

Under the agreement, all nuclear weapons use, threat of use, testing, development, production, possession, transfer and stationing in a different country are prohibited.

For nuclear-armed nations that choose to join, the treaty outlines a process for destroying stockpiles and enforcing the countries’ promise to remain free of nuclear weapons.

In its statement, ICAN called the treaty a “much-needed alternative to a world in which threats of mass destruction are allowed to prevail and, indeed, are escalating.”

The prize came against the backdrop of the most serious worries about a possible nuclear conflict since the Cold War, punctuated by a bellicose standoff between the United States and North Korea.

The North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un, has defied United Nations sanctions prohibiting his isolated country’s repeated nuclear weapons and missile testing, and he has threatened to strike the American heartland with the “nuclear sword of justice.”

President Trump has said he would have no choice but to “totally destroy” North Korea if the United States or its allies are attacked.

Berit Reiss-Andersen, chairwoman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, told reporters that the award was not intended to send a message directly to Mr. Trump. “We’re not kicking anyone in the legs with this prize,” she said. The committee instead intended to give “encouragement to all players in the field” to disarm.

Proponents of the treaty have said that they never expected any nuclear-armed country would sign it right away. But they argued that the treaty’s widespread acceptance elsewhere would increase the public pressure and stigma of possessing nuclear weapons.

The coercive power of such public shaming, treaty supporters said, eventually would lead the holdouts to change their positions and disarm. The same strategy was used by proponents of the treaties that banned chemical and biological weapons, land mines and cluster bombs.

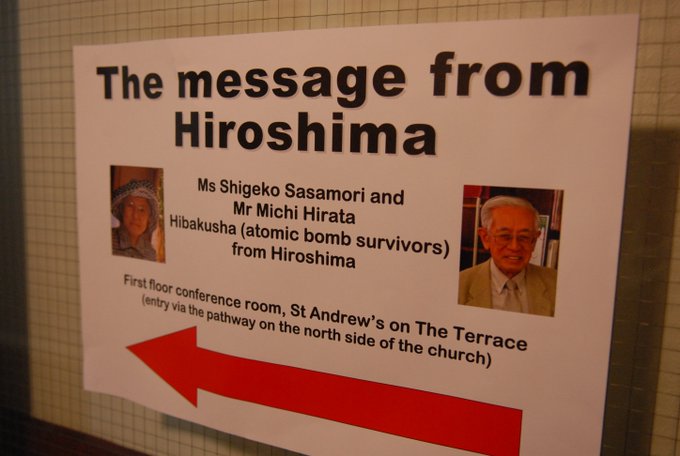

Nuclear weapons have defied attempts to contain their proliferation since the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan in 1945, which led to Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II.

The unspeakable destruction wrought by those weapons laid the foundation for the nuclear arms race and the doctrine of deterrence, which holds that mutually assured destruction of nuclear-armed antagonists is the only way to prevent an attack.

Proponents of that doctrine contend it has basically kept the peace for more than 70 years.

Besides North Korea, Russia and the United States, the other nuclear-armed states are Britain, China, France, India, Pakistan and Israel.

The United States had leaned hard on its allies, especially non-nuclear powers, to boycott the treaty talks that began at the United Nations earlier this year. At the time, Nikki R. Haley, the Trump administration’s envoy to the United Nations, questioned whether the countries supporting the talks were acting in the interests of their own citizens.

Russia and China are equally opposed to the efforts to ban nuclear weapons through an international treaty.

But on this issue, the naysayers are in the clear minority.

The United States was also isolated in 1997, when the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to a civil society group that pushed to abolish land mines. That prize went to the International Campaign to Ban Landmines and its coordinator, Jody Williams.

The international agreement that her group pushed for, the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction, known simply as the Mine Ban Treaty, has been signed by more than three-fourths of all countries around the world. The United States, Russia and China remain outliers.

The mine ban group was among the first to congratulate ICAN on its victory.

It is unusual for organizations to receive the prize. Others have included the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Since 1901, 104 individuals and more than 20 organizations have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Who else has won a Nobel this year?

■ Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W. Young were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine on Monday for discoveries about the molecular mechanisms controlling the body’s circadian rhythm.

■ Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne and Barry Barish received the Nobel Prize in Physics on Tuesday for the discovery of ripples in space-time known as gravitational waves.

■ Jacques Dubochet, Joachim Frank and Richard Henderson were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry on Wednesday for developing a new way to construct precise three-dimensional images of biological molecules.

■ The English novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, known for his spare, elliptical prose style and his inventive subversion of literary genres, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature on Thursday.

Who won the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize?

■ President Juan Manuel Santos of Colombia was honored for pursuing a deal to end 52 years of conflict with the leftist rebel group known as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, the longest-running war in the Americas, just five days after Colombians rejected the agreement in a shocking referendum result.

When will the other Nobels be announced?

One more will be awarded, next week:

■ The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science will be announced on Monday in Sweden. Read about last year’s winners, Oliver Hart and Bengt Holmstrom.

No comments:

Post a Comment